Update added 18 Nov 2018, 13:15 UT:

The launch of SSO-A with Orbital Reflector has been postponed, untill after Thanksgiving.

Update added 27 Nov 2018, 12:00 UT:

New launch date of SSO-A with Orbital Reflector is on 28 Nov 2018 at 18:31:47 UT

|

| Artist impression of Orbital Reflector. Image: Nevada Museum of Art |

In just a few days from now, on

19 November 2018 at 18:32 UT, 28 November 2018 at 18:31:47 UT

Spaceflight Industry's

SSO-A SmallSat Express, a

cubesat rideshare mission, will launch from Vandenberg SLC 4 on a SpaceX Falcon 9. SSO-A will release as much as 64 small spacecraft into space, over a 5-hour period, from two free-flying launch dispensers.

Onboard SSO-A is

Orbital Reflector, a

project by my artist friend

Trevor Paglen. It is an interesting object, for several reasons. It is a cubesat that will inflate a large oblong balloon of about 30 by 1.4 meter, a bit shaped like an obelisk. The balloon is made of a very lightweight, Mylar-like foil that is highly reflective. Hence the name:

Orbital Reflector. When reflecting sunlight, it should be easily visible from earth.

Orbital Reflector is

Art. It is a sculpture in space, one that, in theory, you can see from everywhere in the world (but about reality: see later in this blog post). Trevor teamed up with the

Nevada Museum of Art for this project, and it might be the

first time a Museum has created an exhibit in Space.

|

| Artist Trevor Paglen and an early spherical precursor prototype of the balloon (now at the Nevada Museum of Art) |

Orbital Reflector will be released in a circular,

575 km

altitude, sun-synchronous orbit with an orbital inclination of 97.6

degrees. The anticipated moment of release from the Lower Free Flying

Dispenser (LoFF) is about 2h 18m (or about 1.5 revolutions) after launch, i.e. 20:50 UT, over Antarctica. At what moment the balloon will be inflated once

Orbital Reflector has been released from the LoFF, is unknown to me.

My estimated initial orbit for the object:

ORBITAL REFLECTOR

1 70000U 18999A 18323.77222222 .00000000 00000-0 00000-0 0 09

2 70000 097.6000 032.4835 0001438 157.1159 325.9970 14.97378736 01

UPDATE (27 Nov 2018):

ORBITAL REFLECTOR

1 70000U 18999A 18332.77207176 .00000000 00000-0 00000-0 0 00

2 70000 097.6000 041.3000 0001438 157.1159 325.9970 14.97378736 04

... but once the balloon is inflated, the orbit will rapidly change.

The Falcon 9 Upper Stage is deorbited at the end of the first revolution (see map below), near Hawaii. The deorbit-burn might be visible from eastern Europe around 19:50 UT.

|

| click map to enlarge |

Orbital Reflector should initially have been launched in the spring, but launch delays pushed the date to 19 November.

Unfortunately, due to this and due to the particularities of the orbital plane it is launched

into, visibility of the satellite will initially be very bad, and will remain so for weeks.

The satellite will be making late evening passes

(around 21:15 local time), remaining in the

Earth's shadow and hence unilluminated by the sun in the northern hemisphere. New Zealand, southern Australia and South America in the southern

hemisphere may have

some spotting opportunity. But for Europe and the USA, initial spotting opportunities will be zero. It is the wrong season to see a satellite in this kind of orbital plane.

So the crucial question is: will

Orbital Reflector survive long enough to carry over to spring and early summer, when viewing conditions are more positive? To answer this, I have done some

modelling to get an indication of what orbital lifespan to expect.

SRP and modelling lifespans

Orbital Reflector in itself will be an interesting object to follow due to its highly unusual area-to-mass-ratio. Unlike typical satellites (which do experience SRP too but to a clearly lesser degree), this object will be under significant influence of

Solar Radiation Pressure (SRP). And SRP will have a clear impact on its orbital lifetime, as we know from both theory and from data on the orbital evolution of earlier inflatable balloon satellites.

Earlier balloon satellites were

Echo 1 (1960-009A),

Echo 2 (1964-004A), and

PAGEOS (1966-056A). Like

Orbital Reflector, Echo 1 and PAGEOS were 30 meters wide. Echo 2 was slightly larger at 40 meters. They were spherical in shape, not oblong like

Orbital Reflector. They also initially orbitted at much higher altitudes than

Orbital Reflector will do: an initial altitude of 4225 km for PAGEOS, 1030 x 1315 km for Echo 2 and 1540 x 1670 km for Echo 1.

|

| Echo 2 during development tests in 1961. Image NASA |

The orbital evolution of all these three balloon satellites showed a

strong influence of SRP on the evolution of apogee and perigee altitudes. SRP "pushes" and "pulls" on apogee and perigee of the

orbit, with a quickly changing orbital eccentricity as a result. The effects can be well seen

in the orbital history for Echo 1 and 2 and PAGEOS (source of orbital data used to make these diagrams is JSpOC):

|

| click diagram to enlarge |

|

| click diagram to enlarge |

|

| click diagram to enlarge |

A clear pattern is visible where the orbital eccentricity highly oscillates due to SRP. It initially is quickly pumped up, lowering perigee and raising apogee, then gets back to lower values again, and this cycle then repeats.

Something similar will happen to

Orbital Reflector. SRP will quickly push perigee down and apogee up, pumping up the orbital eccentricity. The progressively lower perigee at the moments SRP pumps up the eccentricity, will speed up orbital decay.

I used

GMAT 2018a to model the effects of SRP on the orbital evolution of

Orbital Reflector. That is not something trivial to do, as there are a number of 'unknowns' involved for which I had to make educated guesses. The results below should be taken very cautiously for that reason.

For example, SRP depends on attitude of the spacecraft with regard to the direction of the sun. That attitude will change over time, and there is the question whether the oblong balloon will be (and stay) in stable attitude or start to tumble. SRP in itself creates a torque and might induce tumbling. Issues like these will strongly influence the amount of SRP, drag, and as a result the orbital lifespan.

There are some uncertainties in the mass of

Orbital Reflector as well: depending on whom you ask, it is either 2.2 or 3.2 kg. This is important, because SRP is highly dependent on the area-to-mass ratio (and so is the effect of drag on the object). If the balloon indeed settles in a least-drag orientation after deployment, as the designers expect, the drag surface is a constant 1.97 square meter.

Because

Orbital Reflector is oblong, and because of the orientation of its orbital plane with respect to the sun, the SRP surface will vary between (almost) minimum and maximum values over one orbit. I have tried to accomodate this by running the model with an SRP surface that is 50% of the maximum value, i.e. 50% of 21 square meter = 10.5 square meter.

To show the non-triviality of SRP, I first ran the model

without SRP, then with SRP, for comparison.

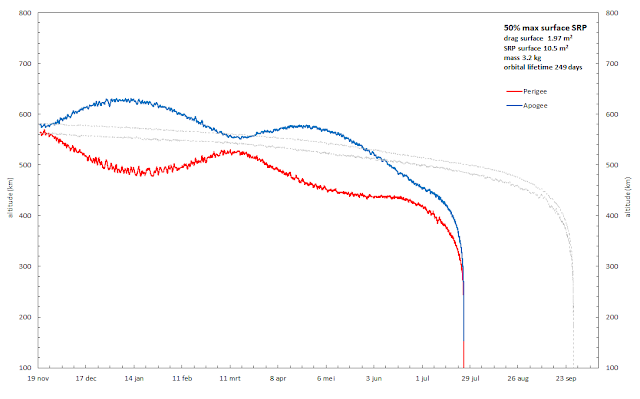

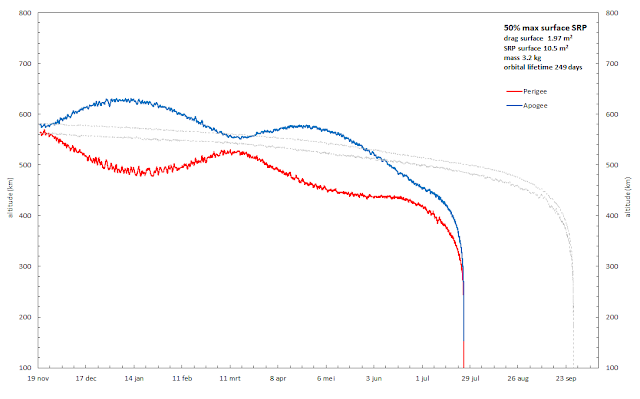

Below are the model results for

Orbital Reflector (expressed as apogee and perigee altitude against date)

if we ignore Solar Radiation Pressure, for two mass values: 2.2 and 3.2 kg.

|

| model results for a mass of 2.2 kg and no SRP taken into account. Click diagram to enlarge |

|

| model results for a mass of 3.2 kg and no SRP taken into account. Click diagram to enlarge |

Below are the results if we

do implement modellation of Solar

Radiation Pressure. The expected lifetime clearly shortens, by up to a third, and this is

because of the progressively lower perigee as SRP pumps-up the

eccentricity of the orbit. The grey lines in the diagrams are the data without SRP from the previous diagrams, as a reference:

|

| model results for a mass of 2.2 kg with SRP taken into account. Click diagram to enlarge |

|

| model results for a mass of 3.2 kg with SRP taken into account. Click diagram to enlarge |

These outcomes should be viewed with caution, as the modelling includes educated guesses and, to quote Monty Python, "

it is only a model". It will be very interesting to see how the real orbital evolution compares to these model outputs.

What these model results do suggest, is that it is possible that

Orbital Reflector, if it inflates and stays intact, might remain on-orbit

long enough to carry it into the more favourable part of the year (late spring and/or summer of 2019) for visual sightings. So let's root that my models resemble reality, as I surely would like to see and image

Orbital Reflector in the sky.

From the artist impressions, the balloon is flat-sided. This could mean that reflections might be specular, and bright only briefly in narrow zones on Earth, much like Iridium flares.

Sat for Art's sake?

Orbital Reflector is

Art. It is distinctly

non-utilitarian, in the common sense of that word: it just orbits. But it does have a deeper purpose than that. As Trevor

recently put it himself:

"Orbital Reflector was designed as a provocation. An opportunity to think about outer space, the geopolitics of the heavens, and the militarization of earth orbits. It’s a project about public space, and a project about who gets to exercise power over our planetary commons, and on what terms"

In other words,

Orbital Reflector is not just there to reflect light to people on Earth; it is also

meant to make people reflect, pondering questions such as "

who owns space?" and "

what is happening out there?".

The question raised by Trevor is pertinent. Space

is Public Space. At

the same time, it is not public at all, but strongly the domain and playground of

Nation States, and notably of the military of those Nation States.

Space is

highly militarized. Not so surprising of course as the whole Space Age

has its roots in the development of Ballistic Missiles. The role of the military in Space and Space innovation is often overlooked. While many

people look at NASA as the big innovator in the US Space program, the real innovations

in Space are often the product of another Space Agency, the

NRO, which is NASA's

shadier military cousin and generally unknown to the broader public, even though it sends billions worth of hardware per year into space. Hardware that plays a prominent role in geopolitics and modern warfare. They include highly detailed optical and radar imaging satellites, navigation satellites, communication satellites and giant listening radio "ears" in space. Long-time readers of this blog know what I am talking about.

|

| Pondering Space and other things. Trevor Paglen (right) and the author of this blog (left), June 2018 |

It is very interesting that

the only areas where it is internationally regulated what can and cannot

be done in space, concern weapons in Space and

national sovereignty in space. And this was done over 50 years ago

already, as part of the 1967 “

Treaty on Principles Governing the

Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space,

including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies” (or “

Outer Space Treaty” in short).

The

fact that after more than 60 years of Space exploration

still

only the

military/national sovereignty aspect has been regulated,

tells you how dominant that aspect of the use of space is. Nobody bothered to regulate other

potential aspects of space (such as private enterprise).

We are however at a

crossroads. Ideas for mining asteroids and for private crewed missions to Mars and the Moon (previously only in the realm of Nation States) have raised the topic of private enterprise

in space, and raised specific questions about regulating the

exploitation of resources in Space and protection of historic sites in Space. We are standing at a decisive moment

in the use of space too now that purely commercial, privatized space

outfits have appeared on the launch market, taking over from companies

closely alligned to what Eisenhower called the “Military-Industrial

Complex”: new outfits like SpaceX, Rocket Lab and a number of other

startups.

But this does not mean that the private sector

takes over from the military. Some of these private firms (e.g. SpaceX)

have been quickly drawn into the military sphere themselves, with lucrative

launch contracts from the US military. Orbital ATK recently has been bough by Northrop

Grumman, part of the "Military Industrial Complex" for decades. Meanwhile, three major spacefaring nations, the USA, China and Russia, have increased their military posturing in space, with ASAT tests and increased suggestions within the US military that the US should re-negotiate or even leave the Outer Space Treaty, as it is seen as restrictive to a more active, offensive use of space.

It is therefore a

crucial time to bring up questions about who governs space, what is and

what isn’t allowed there, who gets to put things up there, and to put to question the overarching role of the military

in this all.

Paglen's

Orbital Reflector encourages you to reflect upon these issues.

Note: I warmly thank Trevor Paglen, Amanda Horn, Zia Oboodiyat, Mark Caviezel and Ted Molczan for discussions and for providing viewpoints and data.

Edits of 27 Nov 2018: revised launch time, revised elset estimate, new map, and statement that the deorbit-burn might be visible from N-Europe